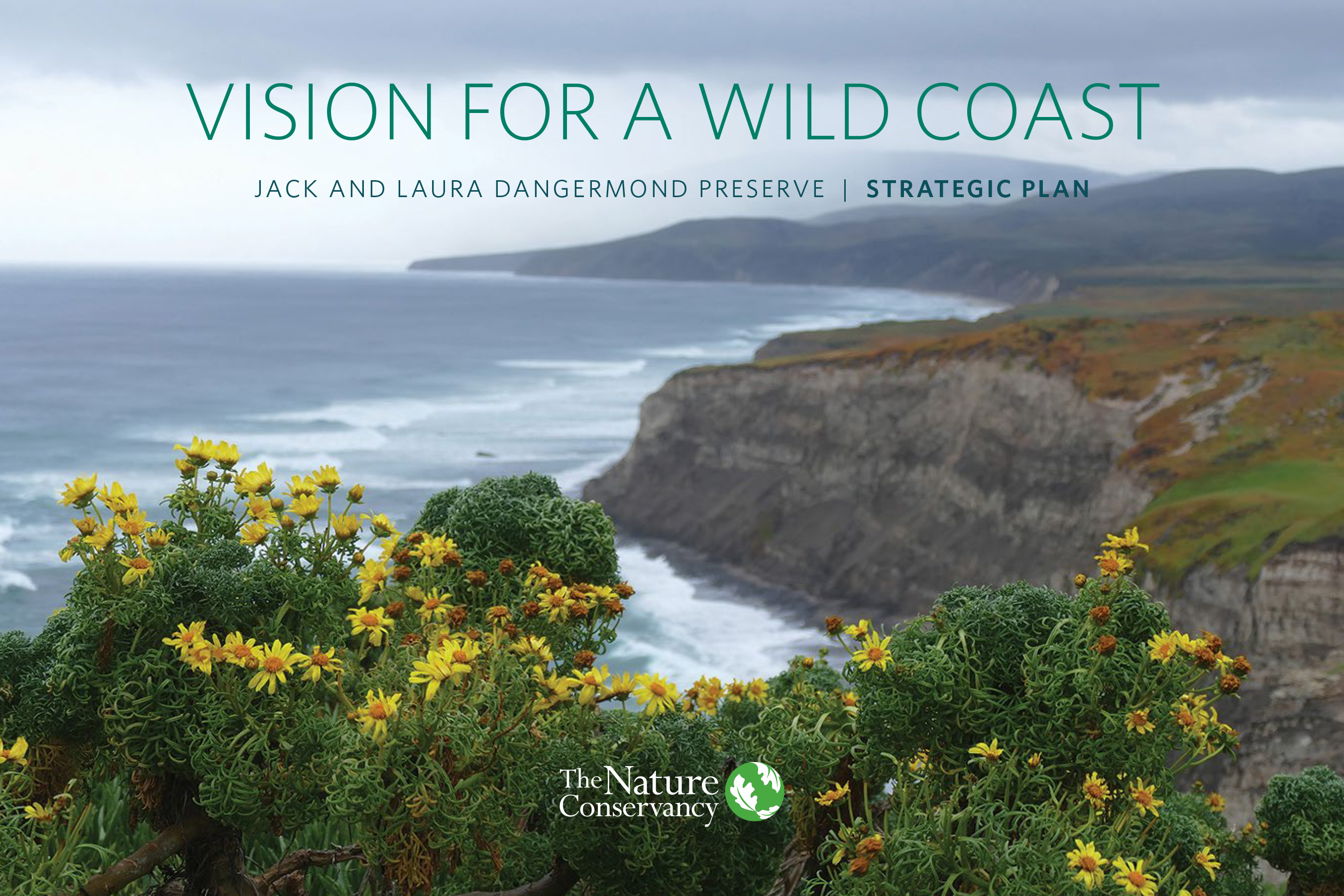

Serving as a global platform for applied conservation research and education to inspire the next generation of conservation leadership, the Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve is an enduring nature preserve protecting intact and resilient natural resources—last-of-their-kind coastal ecosystems, natural communities and species, and significant cultural resources—at a dynamic, ecological crossroads between land and sea and northern and southern coastal California at Point Conception.

Download

Preserve Overview

There aren’t many places on the Southern California coast that remain largely untouched by development. The Nature Conservancy’s (TNC’s) Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve is one of them—exceptional in size, location, and biodiversity. The Preserve is a vast property that sits at Point Conception—the sharp corner of coastline that gives California its distinctive crook. The land has been kept intact, free from significant development for nearly 100 years.

Located near Santa Barbara, Point Conception and its surrounding lands comprise one of the last and best “wild coast” areas in Southern California and have some of the highest biodiversity and cultural values in the world. The Preserve’s unusual geography makes it a globally important site for conservation. The coastline runs north-south above Point Conception and east-west below it; cold currents from the north collide with warm water from the Santa Barbara Channel, creating diverse marine and terrestrial habitats unlike any others in the state. The Preserve stretches from the coast to the Santa Ynez Mountains and includes chaparral, grassland, oak woodlands, coastal scrub and closed-cone pine along eight miles of wild coastline.

Dangermond Natural Resources by the Numbers

-

24,000+

24,000+ acre coastal property

-

8+

8+ miles of undisturbed coastline with sandy beaches

-

50

50 miles of streams

-

300

300 acres of wetlands

-

9,000

9,000 acres of native and annual grassland

-

6,000

6,000 acres of oak woodland and forest

-

200+

More than 200 wildlife species

-

600

Nearly 600 plant species

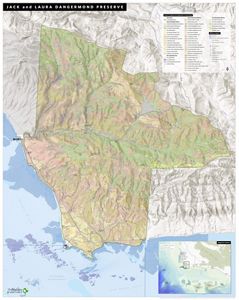

Regional Context

The Preserve is a 24,000 + acre property located in Santa Barbara County, California. The Preserve encompasses more than eight miles of the coast surrounding Point Conception, adjacent to Jalama Beach County Park in the north. Most of Jalama Watershed and contributing tributaries fall within the Preserve. The 100,000-acre Vandenberg Space Force Base (VSFB) abuts the western boundary of the Preserve and the offshore Point Conception State Marine Reserve protects over 22 square miles of coastal and marine habitat creating contiguous terrestrial-marine protection.

The Preserve helps to maintain significant regional connectivity for many species. Maintaining open and undeveloped land is important for wildlife populations and, over longer time periods, for plants, to ensure that genetically diverse populations can persist. Ensuring that lands are effectively managed to maintain habitat connectivity, either through some permanent conservation action (such as acquiring land for a nature preserve) or through the compatible management of private lands, is a critical conservation goal. Given its important regional context, especially for habitat connectivity for wide-ranging species, the Preserve is developing important regional partnerships with neighbors and agencies to protect the unique biodiversity of the region.

Ecological Context

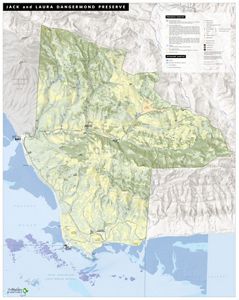

Most of the Preserve is located on the Lompoc Hills and Point Conception U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) 7.5-minute topographic quadrangle maps. The easternmost portion of the Preserve is located on the Santa Rosa Hills and Sacate quadrangle maps. Elevation varies from sea level to approximately 1,680 feet at the crest of the Santa Ynez Mountains.

The Preserve sits at the boundary of three USGS terrestrial ecoregions, the Central California Foothills and Coastal Mountains (CCF), the Southern California Mountains (SCM), and the Southern California/Northern Baja Coast (SCB). This unique positioning is mirrored in the ocean with Point Conception sitting at the breakpoint of the Northern and Southern California Current ecoregions, which creates high marine biodiversity due to the meeting of the northern and southern ranges of many species.

The southward flowing and colder California Current moves offshore at Point Conception, while the nearshore shelf is bathed by the warmer California countercurrent (CA-MLPA 2009, Claisse et al. 2018). This location is a biogeographic crossroads that serves as a “mixing” zone, or ecotone, between cooler, more maritime climate adapted terrestrial and freshwater species of the Central Coast and species adapted to the warmer and drier South Coast and Northern Baja California region.

Vegetation types common in the general region surrounding the Preserve are a mosaic of oak woodlands, annual grasslands, chaparral and coastal shrublands, and scattered patches of conifer forests at more mesic sites and at higher elevations. The primary USGS terrestrial ecoregion for the Preserve is the CCF, which spans all the way around the foothills of the Central Valley, on both the Sierra Nevada (eastern) side of the Valley and on the western side (Inner Coast Range) to the Pacific Coast south of the Santa Cruz Mountains (WRA 2017). This ecoregion reaches its southernmost point on the Preserve at Government Point.

The CCF ecoregion is one of four Mediterranean ecoregions occurring within California. This portion of California is one of five Mediterranean climate regions globally, which encompass only 2% of the world’s land area but 20% of the world’s plant species (e.g., Rundel 2018). The Mediterranean biome is among the most imperiled globally (Hoekstra et al. 2005), and is recognized as a biodiversity hotspot, with high endemic species diversity and endangerment.

Overview Maps of the Dangermond Preserve

Some of the many views of the unique geography of the Dangermond Preserve.

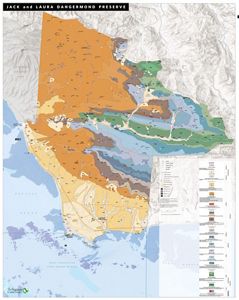

Dangermond Preserve Vegetation: Dangermond Preserve Vegetation Map with over 50 vegetation communities represented. © Megan Webb/TNC

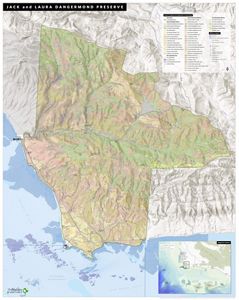

Dangermond Preserve Map: Dangermond Preserve General Overview Map. © Megan Webb/TNC

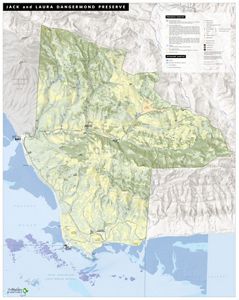

Dangermond Preserve Geology: Geologic formations of the Dangermond Preserve. Original mapping done by Thomas Dibblee in the 1970s. © TNC

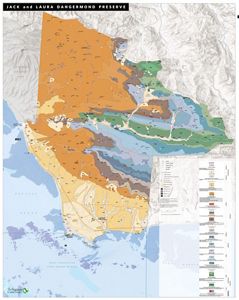

Dangermond Management Zones: Management Zones of the Dangermond Preserve. © Kelly Easterday/TNC

Context continued…

The varied climatic, geologic, soil, and topographic conditions at the Preserve and surrounding lands drive tremendous species diversity. Over 1,300 plant species, more than 500 bird species, 138 terrestrial and marine mammals, 43 reptiles, 17 amphibians, and over 20 freshwater fish species have been documented in Santa Barbara County, including roughly 30 endemic animal species and 35 endemic plant species. As climate conditions change, some of these species may shift their ranges accordingly, possibly to relatively cooler, more mesic areas, provided that underlying abiotic conditions and interspecific competition do not deter their movement and establishment (Loarie et al. 2008). The region the Preserve covers is one of the most natural, least protected parts of the California coast south of Humboldt County.

The Preserve serves as core and migratory habitat for wide-ranging mammal species including mountain lions, bobcats, coyotes, deer, black bears, badgers, and several species of bats. Riparian woodland, annual grassland, oak woodland, and other habitat areas of the Preserve serve as a migratory stopover and breeding areas for neotropical migratory songbirds. The beaches, rocky intertidal, and other coastal habitats support flocks of migrating and over-wintering shorebirds and critical haul-outs for local and wide-ranging marine mammals such as harbor seals and elephant seals. The value of these habitats to wide-ranging and migratory species varies seasonally and by habitat quality but the Preserve, by its size and concentration of high-quality habitats, is a stronghold for these species.

Land Use History at the Dangermond Preserve

Pre Mission

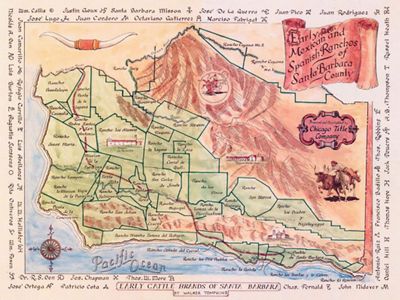

The Preserve stands on the ancestral lands of the Chumashan people, a collection of sovereign tribal entities who lived on this land prior to Missionization and have lived in the greater region for over 13,000 years.

Explorations

An expedition by Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo in 1542 opened the door for many voyages spanning the next 200 or so years leading up to the Portola’ (1769) overland expedition that primed the region for the building of missions.

Periodic contacts between Europeans and Chumash continued through 1769, when the first Spanish land expedition was led through the area by Gaspar de Portola.

Spanish and Mexican Era

The establishment of missions followed in the next 35 years, some Chumash elected to relocate into missions while others were coerced into relocating.

Rancho Punta de la Concepción (29,992 acres) was granted to Anastasio Carrillo of the Santa Barbara Presidio in 1837. It included the southeast corner of Rancho El Cojo (8,580 acres) and a portion of the Jalama Ranch.

Early American Era 1850

Many changes followed the establishment of California statehood in 1850. The Point Conception Lighthouse was completed in 1852, and by 1899 construction had begun on the Southern Pacific Railroad, reaching the Point Conception area in 1901.

Modern Ranching

In 1913, Fred Bixby acquired the Cojo Ranch, followed by the acquisition of the Jalama Ranch in 1939. The Cojo-Jalama Ranches supported cattle herds of varying sizes and crop agriculture throughout the 1900s.

Staff Stories

From Flow to Flame: Linking Hydroclimatic Changes to Wildfire Risk

By Mahsa Khodaee, Spatial Data Analyst at TNC's Point Conception Institute (PCI)

The threat of catastrophic wildfires is a persistent concern, especially in California, where shifts in climate patterns significantly impact ecosystems, creating conditions that heighten wildfire risks and alter fire behavior. Despite progress in understanding these dynamics, applying scientific knowledge to real-world solutions remains challenging. The Point Conception Institute (PCI) aims to bridge this gap by combining rigorous scientific research with actionable, on-the-ground conservation strategies. This approach allows PCI to play a crucial role in translating data-driven insights into effective management practices, making it a key player in regional conservation efforts.

As a Spatial Data Analyst at PCI, I leveraged geospatial analysis to study the interplay between climate shifts, water resources, and wildfire risk. My passion for this work comes from a deep interest in the ecohydrological processes of forested ecosystems, a focus that guided my Ph.D. research. My time at PCI enabled me to build on this expertise to develop insights and tools that support prescribed burn planning and risk reduction at the Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve (JLDP). This role provided valuable opportunities, allowing me to apply my academic background to real-world challenges and collaborate closely with other scientists and land managers.

My role involved integrating climate trends from hydrometeorological data into wildfire models, addressing the need to understand how extreme weather events shape wildfire risk. While droughts are known to elevate risks, the impacts of rapid vegetation growth, heavy rainfall, and subsurface water are less understood. Even in data-rich California, significant knowledge gaps persist due to the complexity of these interactions and limited historical records. Our work aimed to address these gaps by studying how long-term shifts, like changes in groundwater recharge, affect fire probabilities. We aim to transform these findings into practical tools—interactive maps and applications—that help land managers make informed decisions about risk reduction.

Advancing our understanding of climate impacts is essential for building resilience, closely aligning with PCI’s mission to drive effective conservation. The regional wildfire risk analysis and insights we developed offer critical information for strategic decision-making and targeted risk reduction efforts.

See the full paper here.

Jalama Creek Barrier Removal

Q&A with Laura Riege, Dangermond Preserve Project Manager

Where exactly are you removing these from?

These two barriers are a ½ mile up from the estuary, and 1-½ miles up from the estuary. We are working with Vandenberg Space Force Base to gain access to the first barrier and Santa Barbara County for the second barrier which is associated with a county bridge.

What are the differences between Steelhead and Rainbow Trout?

Steelhead and rainbow trout are the same species with two different life histories. Both start their life in freshwater. Steelhead migrate out to the ocean (like salmon) and come back to their native stream to spawn while rainbow trout stay in freshwater their entire life. Steelhead go out to the ocean as smaller fish and come back larger so they can produce a great deal more and larger eggs which helps maintain population numbers. Steelhead are literally a connection between terrestrial freshwater and marine systems; juveniles provide land-based food for marine system and adults provide marine-based energy base to otherwise energy depauperate streams. Steelheadcan “stray” into other streams to spawn (lay eggs) if they can’t access their native stream and rainbow trout can remain in the natal stream to reproduce even when sections dry out and individuals cannot reach the ocean This diversity and flexibility of life history confers resilience in California’s dynamic climate and streams.

Why do we want to create a stronghold of steelhead at the Dangermond Preserve?

Creating a Steelhead stronghold on the Dangermond Preserves allows us to maintain a healthy regional population in a conserved watershed in case other habitats in California are compromised by catastrophic fire, drought or development. The last steelheadwas observed in the Jalama Creek in the 1997. This habitat restoration can create a source that can stray to neighboring watersheds which are also being restored. Removing these barriers to migration will enable straying of steelhead from other existing populations into Jalama Creek in time from Jalama Creek to other watersheds. This connectivity will benefit the recovery and resilience of populations throughout the region of the federally endangered Southern California Coast steelhead Distinct Population Segment.

Once there is a stronghold at the Dangermond Preserve, we would be open to translocations of the species where they are needed.

How can this help in the face of climate change?

Restoring watershed health by removing fish passage barriers can build resiliency against drought and catastrophic fires. If fire or subsequent mudslides impact one watershed or part of a watershed, then it may be repopulated in time by other connected areas or watersheds. Building in redundancy, to drought and fire and climate change.

Where are Steelhead found?

They range from habitats in Mexico to Russia. In the US they are managed in regions or “Distinct Population Segments.” The distinct population segment (DPS) for Southern California is federally endangered. The remaining DPS in California are each federally listed as threatened

Why are Steelhead so special?

They are different from other salmon because they go back and forth between the ocean and freshwater. They also spawn multiple times.

How is this related to groundwater and SGMA?

The Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve is a living laboratory where we are connecting many different research avenues to better understand the whole and how to inform conservation and management. At JLDP we are monitoring groundwater and how that affects streamflows. We can then connect that to conservation science and best management practices that help steelhead rainbow trout population resilience.

Why are the dams there in the first place?

One of the dams appears to have been placed for easy access to fresh water to resupplysteam locomotives that ran on the nearby railroad. The second barrier is associated with a Santa Barbara County Road where they added concrete to prevent erosion on the bridge abutments; which instead eroded the stream creating a barrier that steelhead could not jump over.

Point Conception Institute Anthony LaFetra Research Fellowship

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) is pleased to announce that the inaugural Point Conception Institute Anthony LaFetra Research Fellow is Dr. Erica Nielsen, a coastal marine scientist who shares the deep passion for California and its native wildlife that Anthony LaFetra personified throughout his life.

Serving for 57 years with the Rain Bird Corporation, including as president and chief executive officer, Mr. LaFetra evolved Rain Bird from a local company based in Glendora into a global irrigation leader promoting water efficiency. In addition to his decades of leadership with Rain Bird, Mr. LaFetra was a gifted fly fisherman, an avid skier, and a lover of nature, as well as an engaged philanthropist who supported land preservation, native wildlife, and education. Mr. LaFetra passed away at age 80 in January 2021, survived by his daughter and son, his sister and her husband, and four grandchildren.

In September 2022, Mr. LaFetra’s family made a generous gift of $1,900,000 to TNC to establish an endowment for the Point Conception Institute Anthony LaFetra Research Fellowship, which will support a term fellowship that offers graduate and postgraduate researchers the remarkable opportunity to synthesize data and advance knowledge about coastal ecosystems and how they can be restored and protected in the face of a changing climate and other threats.

After a highly competitive search that attracted dozens of applicants from around the country, Dr. Erica Nielsen was selected as the program’s first fellow. Dr. Nielsen’s fellowship will be based at the Point Conception Institute, a global conservation

science center based at the Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve in Santa Barbara County.

Dr. Nielsen has extensive experience in coastal marine science and is a field leader in bringing advances in molecular ecology to systematic conservation planning. She holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in zoology from Stellenbosch University in South Africa and a B.Sc. in biology from the University of California, Santa Cruz. For her graduate work, Erica pioneered the integration of marine species’ genetics into conservation planning, or “seascape genomics.” Dr. Nielsen most recently served as a postdoctoral associate at the University of California, Davis.

As the climate crisis takes hold around the world, there is a pressing need for living laboratories where the future of resilience and sustainability can be designed. Protected areas like Dangermond Preserve can serve as proving grounds for bold conservation action and engines of knowledge generation if their data and lessons learned circulate beyond their borders.

During her two-year fellowship, Dr. Nielsen will lead coastal research collaborations with the Point Conception Institute and leverage and synthesize data on coastal biodiversity, species range shifts, and climate change to increase the pace, scale, and effectiveness of conservation.

As a fellow Californian, Dr. Nielsen embodies many of the same values as Anthony LaFetra: a love for California’s natural heritage and native wildlife, a passion for education, and both a local and global perspective. The Point Conception Institute Anthony LaFetra Research Fellowship will serve to advance the conservation of biodiversity and critical eco- system processes and functions—and provide an

unparalleled legacy of research and collaboration for future generations.

By Jinsu Elhance, Conservation Technology Associate at the Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve

Collecting Drops of Data at the Dangermond Preserve

Every drop of water and every byte of data has a story, interwoven with the tapestry of our environment. Both possess the power to shape the world around them at each stage of their life cycles. As rainwater disappears into the earth before flowing through creeks and rivers, its journey parallels the flow of data among conservationists, researchers, land stewards, and policymakers. Each step in this data cycle contributes to our understanding of water and its conservation. At the Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve, The Nature Conservancy’s preserve in Santa Barbara County, where native ecosystems have been protected from extensive development, scientists are pioneering a concept known as the Freshwater Digital Twin — a groundbreaking tool that merges the narratives of water and data into a transformative whole.

A Digital Twin is an interactive 3D map of a system. While these models have been developed primarily for urban infrastructure, the Dangermond Preserve is pioneering their application to complex natural environments. The Freshwater Digital Twin is an online map on which researchers, land managers, and other conservation workers can observe a real-time representation of the preserve’s hydrology. Users can click on points representing sensors installed in streams, tanks, and wells to download the most current data. Users can also view how the preserve changes under different climate scenarios, as the map visualizes potential future water dynamics.

The Dangermond Preserve, encompassing 24,346 acres of protected land, serves as a living laboratory where scientists delve into the mysteries of California's ecosystem dynamics. Nestled at the convergence point of marine and terrestrial ecosystems along the state's coastline, it holds the key to unraveling the intricate relationship between water and life. Within the preserve lies the Jalama watershed, meandering through hilly canyons and lush vegetation before ultimately merging with Jalama Creek and the vast ocean. This setting presents an unparalleled opportunity to study the water system holistically. It is here that I embark on a mission to collect data throughout the basin, constructing a digital model that captures the preserve's water dynamics. This distinctive interpretation of the Digital Twin concept enables us to observe and study the natural environment through a digital abstraction. The future of groundwater in California hinges on the quality of analysis conducted in such invaluable initiatives.

In my prior life as a data scientist, my curiosity was immersed in theoretical models and algorithms. However, I yearned for data science applications that facilitated meaningful contributions to our planet. In my job as a Conservation Technologist at the preserve, I draw upon my knowledge of environmental science, statistics, and technology to address broader questions about how to achieve a sustainable future. Now that I work in the field, I spend my days surrounded by the captivating beauty of untouched landscapes. Venturing into the field allows me to collect data that will underpin the construction of the Freshwater Digital Twin. Our digital twin relies on a water budget model to enhance our comprehension of the intricate relationships between precipitation, streamflow, and groundwater storage.

Today, my journey takes me deep into the chaparral, surveying wells and deploying sensors in riverbeds, capturing the unique stories within every droplet of water. By collecting data from precipitation patterns observed by weather stations, estimating streamflow through an intricate model developed by the Nature Conservancy, and monitoring groundwater levels with pressure transducers installed in wells, we weave together the threads of water's narrative. I embark on an early morning expedition, traversing winding roads in an ATV laden with well-survey equipment. As I arrive at each well, I carefully brush away foliage to deter rattlesnakes before removing the cap from the casing. Spending hours meticulously recording the conductivity, temperature, and depth of the water, alongside details about the sensor, the surroundings, and any noteworthy observations, I capture the essence of each well's story. When I’ve finished, I download the data onto a field computer, from which I’ll later upload it into the models within the Digital Twin. Finally, the sensor is redeployed or replaced, continuing its data collection until the following year.

Like my personal journey intertwining data science and environmental science, the development of valuable digital abstractions like the Digital Twin hinges on ground truth. The data we collect in the field, much like a drop of water, possesses its own unique story. It flows among conservationists, researchers, land stewards, and policymakers, informing their work and thereby creating an impact at every step of its journey. Just as water is essential to life, this data will ultimately contribute, in its own right, to preserving the well-being of our planet.

Dangermond Oak Tree Survey: Preserve Scientist Dr. Elizabeth Hiroyasu and Stewardship Manager Moses Katkowski, leaders of the Dangermond Preserve TREX program, survey the oak trees at Army camp. © 2022 Erin Feinblatt

Controlled Burn Preparation: Elizabeth takes live fuel moisture samples to understand how vegetation will burn to prepare for the controlled burn. © 2022 Erin Feinblatt

Controlled Burn Preparation: Elizabeth and Moses set up a 50-meter transect or controlled area to assess the number of plants and soil quality before lighting the controlled burn. © 2022 Erin Feinblatt

Squad Goals: Some of the squad assembles at Dangermond Preserve before the burn begins. Their shovels are designed for digging fire breaks. © Jenna Allred

Controlled Burn: Jeremy Zagarella, Natural Resources Planner in the Pala Environmental Department for the Pala Band of Mission Indians, lights a controlled fire with the team. © Jenna Allred

Controlled and Contained: Firefighters walk the control line to make sure the burn area is contained. © Emily Aiken

Soil Samples: Elizabeth collects soil samples to study the effect of burning on soil characteristics. © 2022 Erin Feinblatt

After the burn: Elizabeth and Moses perform “mop up,” making sure that the controlled fire is out and the burn piles are safe, under Army camp oaks. © 2022 Erin Feinblatt

After the burn: Elizabeth places the hose over her shoulder for better control of the stream. © 2022 Erin Feinblatt

Fighting Fire with Fire: Controlled burns may help keep oak woodlands free of pests, resulting in a more robust acorn crop. © 2022 Erin Feinblatt

By Ben Miner, Director of the Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve; November 28, 2022

5 Years of Conservation at the Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve

As we near the five-year anniversary of the Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve, we would like to take a moment to reflect on the progress we have made at this 24,460-acre living laboratory. This is my first year as director of this amazing place and it is an honor to help chart the course to so many groundbreaking conservation goals. Take a look at this video to learn about our work at the preserve directly from scientists and staff.